No rock is too small

For these large birding hotspots, we have to head to rugged coastal areas. The Nordic coast is perfect for this. If you go all the way north, you'll end up at Varanger, and then you can't miss Hornøya.

On this island—or rather rock—no fewer than 100,000 birds of 11 bird species breed in an area of 0.4 km². That's a population density of 250,000 birds per square kilometre! Manila, the extremely densely populated capital of the Philippines, has approximately 46,179 inhabitants per square kilometre.

These colonies have their problems, just like our major cities. Colonies are susceptible to infections. Avian influenza outbreaks can have disastrous consequences for bird colonies. In 2023, there was a massive outbreak in northern Norway, primarily affecting kittiwakes.

Another threat to bird colonies is predation. Normally, relatively few visit these cliffs. Gulls are the major predators, and in northern areas, skuas and gyrfalcons also dare to snack on a seabird. The real problem is land predators, and we play an important role. Rats are disastrous, but so are we. Firstly, we are the reason that these nasty rats can colonise these rocky outcrops by boat, and secondly, we (especially in the past) ate a fair amount of seabird food. For the bearded sea dogs, this was a welcome source of protein; one species even had to suffer the consequences: the famous great auk.

Another factor that doesn't help colony-nesting seabirds is that they often lay only a single egg. For this reason, it's crucial to minimise disturbance. On Hornøya, you can only walk along a kilometre-long path; otherwise, the island is inaccessible.

Climate change—surprise, surprise—is also not helping matters. Rising sea temperatures are causing various fish species to change their ranges, which can lead to food shortages for seabirds. Moreover, we sometimes cast our nets a little too enthusiastically into the sea. In other words, we're a major competitor when it comes to food security.

So you see: no matter how impressive these bird supercities may seem, these places are also under immense pressure!

Clowns of the sea

The biggest crowd-pleaser on Hornøya is the puffin. This bird looks rather clumsy as it waddles with its plump body. Puffins owe their immense popularity to their bill, which shows the Belgian tricolour. The exact reason for this bill's bright colours remains unknown, although some suspect it's a kind of quality indicator; the flashier, the bolder.

Another fun fact: the yellow, bare skin at the base of puffins' bills is stretchable, creating more space between the halves of the bill!

It might be a surprise, but puffins don't breed on cliffs; they are burrow-nesters! You will mainly find them on the higher parts above the rocks, where they dig burrows; the tunnels can be over two meters long! This video shows how the digging process works and what such a burrow looks like from the inside.

Penguins of the Northern Hemisphere

Compared to puffins, the razorbill and the guillemot look even more like penguins. Despite the superficial similarities, these birds are not closely related to penguins. Perhaps surprisingly, razorbills and puffins are more closely related to, yes, waders!

Their minimalism makes the razorbill and the guillemot among my favourite birds of seabird colonies. I find the white lines on the razorbill's bill and the white eye line truly beautiful! It gives them a certain mystery, a certain wisdom. Perhaps their true beauty lies within their mouths, their striking yellow palate.

I find the nominate (most common) plumage of the guillemot slightly less attractive, although they are somewhat friendlier than the grumpy razorbill. However, the further north you go, guillemots more often have a white eye ring with a descending white line. If you know I was a fan of white lines on razorbills, you know these "northern" guillemots also enjoy my attention!

As a bonus, you'll also find the Brünnich's guillemot on Hornøya, a die-hard Arctic species that reaches the southern edge of its breeding range here. This species looks like a cross between a guillemot and a razorbill; its bill is more robust than a guillemot's, but not as robust as a razorbill's. The white stripe at the base of the bill is also characteristic. A bird for the lists.

Stinking Beauty

I conclude this blog with a paragraph about the European shag, the smaller cousin of the more familiar cormorant. Unlike our cormorant, the European shag is a real sea dog. This bird greets you the moment you set foot on Hornøya. You see them immediately; the first nests are next to and under the jetty. You hear them too; they make a very ugly nasal screech, but above all, you smell them. And stink they do! In Vardo, they jokingly told me that Hornøya is not only a feast for the eyes, but also for the nose; that last part was said sarcastically.

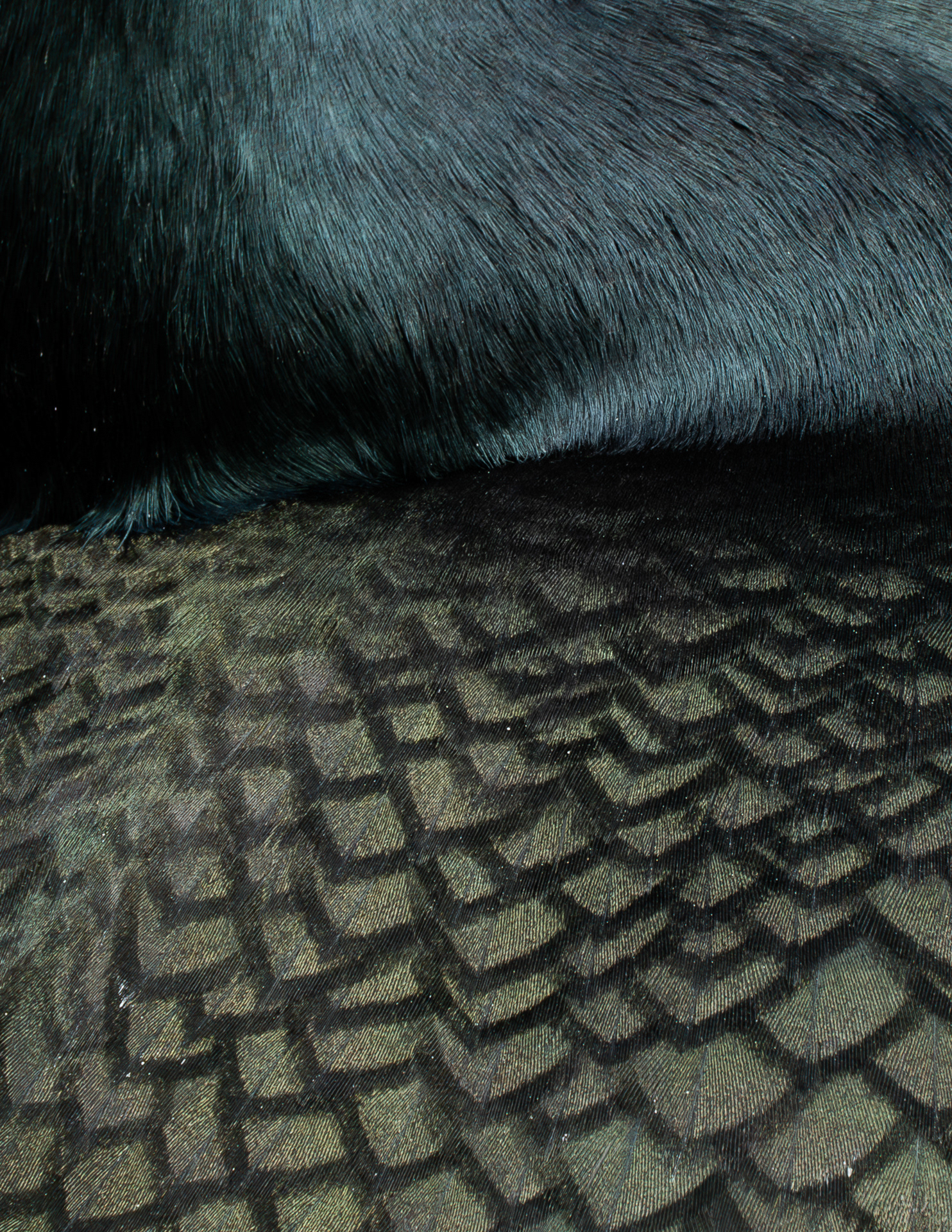

Despite their smell, European shag are incredibly beautiful birds, especially when you observe them up close with the soft sun at their backs. A true spectacle of colour unfolds; the feathers turn from gold to emerald green. The contrast between the delicate neck feathers and the neatly tiled feathers on the back is striking. And I have to admit, I'm almost drowning in those deep green eyes. They're beautiful birds, struggling to attract attention among all those other, much cuter, colony-dwelling birds. Which is a shame, because they're certainly worth a visit!

I'm already eagerly looking forward to my next visit to a seabird colony!

I'm already eagerly looking forward to my next visit to a seabird colony!